By Dr. Timothy S. Huebner

Although he served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1965 to 1969, Fortas’s rise to prominence is a story largely unknown to Memphians and Rhodes alumni. And yet without the transformative experience of his college education and the support of his two Memphis mentors—Hardwig Peres and President Charles E. Diehl—Fortas might never have reached the pinnacle of his profession.

Born in Memphis in 1910 to poor immigrant Jewish parents, young Abe Fortas lived the early years of his life on the margins. His parents had come to America in 1905 to join his father’s brother in the furniture business. But his father, Woolf Fortas, originally from Russia, eventually parted ways with his more successful brother, and young Abe’s family struggled to make ends meet.

Abe, like his four older siblings, did what he could to help support the family. His father introduced him to the violin, and after taking lessons as a boy at a neighborhood church, Fortas acquired enough skill as a violinist to begin earning money teaching others and playing at local concerts. In high school, he became director of a band, The Blue Melody Boys, which played two or three nights a week at a local park, allowing him to earn the impressive sum of $8 an evening. The band also performed at parties, as well as high school and college dances throughout the city. Fortas soon earned the nickname “Fiddlin’ Abe.”

In 1926, at the age of sixteen, Fortas graduated from Southside High School, and that same year Hardwig Peres, a prominent Jewish businessman in town, endowed a scholarship in the name of his deceased younger brother, who had been a local chancery court judge. Fortas beat out 12 other applicants to become the first recipient of the Israel H. Peres Scholarship at Southwestern.

The previous year, Diehl and the trustees had moved the college from Clarksville to Memphis, where a grand campus in the gothic style had begun to take shape. An ordained Presbyterian minister and graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary, he believed deeply in traditional liberal education, and the curriculum for the co-educational student body at Southwestern included two years of Bible, two years of English, and two years of Mathematics, Latin, or Greek, in addition to other requirements. Diehl and the faculty he hired exemplified a form of early twentieth-century liberal Protestantism that exposed Fortas to a combination of intellectual open-mindedness and serious moral reflection.

For the smart and talented Fortas, none of whose family members had gone to college, attending Southwestern proved transformative. Although he apparently lived at home, Fortas jumped into college life with both feet. He used the money he earned from his violin playing to buy a car, and he seemed constantly on the move—from sleeping at home to studying and attending class on campus to playing at local concerts and dances. Fortas excelled in his coursework while also devoting himself to a variety of extracurricular activities.

At first he considered studying music, but Fortas eventually decided to focus on English and political science. His professors loved him. “He had one of the most incisive minds I have ever seen in an undergraduate in all my teaching experience,” history professor John Henry Davis noted. “He saw through things into their deeper aspects more than most men do.” Fortas earned high grades and later expressed a deep appreciation to the Southwestern faculty who, in Fortas’ words, “opened for me new vistas into man’s past and future.”

While achieving academic success, Fortas navigated student life with aplomb. Arriving at college at the age of 16, while most of his peers were two years older, the Jewish teenager joined a Protestant student body of some 400 students, composed of young men and women drawn mostly from the city and the surrounding region. Fortas stayed away from the fraternity scene and the elite campus social clubs—Jews probably would not have been allowed to join—and instead focused on reading, writing, thinking, and arguing.

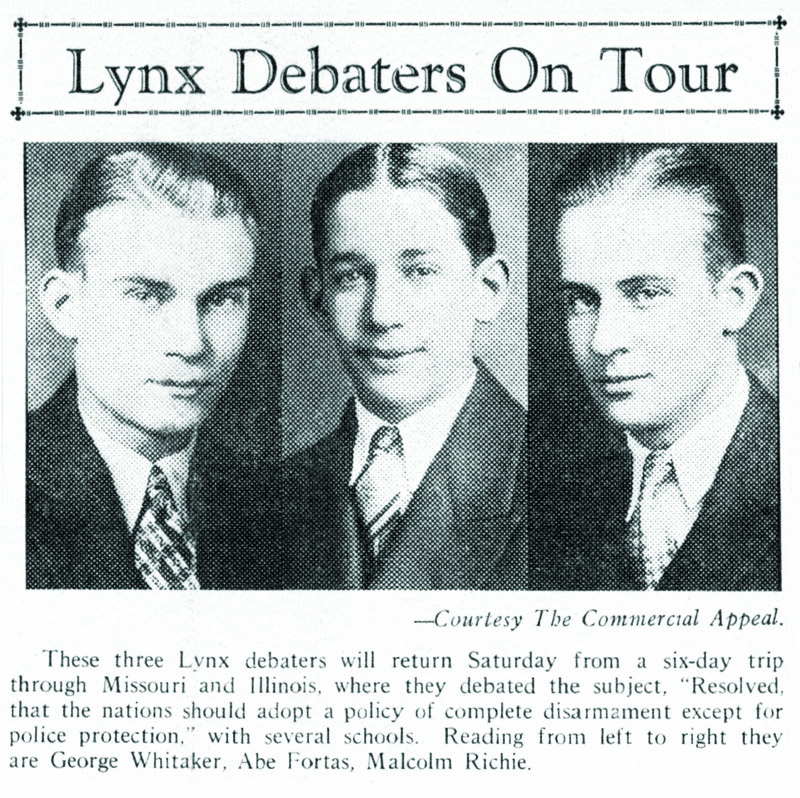

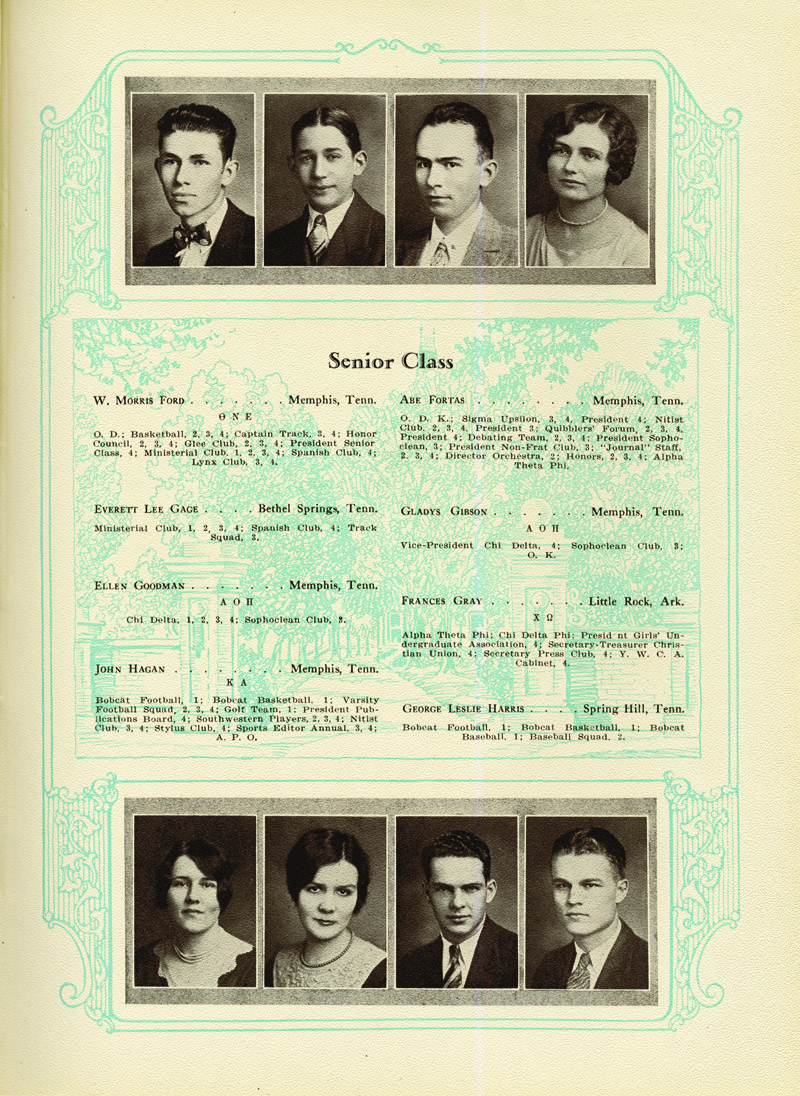

During three years on the college’s newly formed debate team, he reportedly won 17 contests and only lost three, while debating such important topics as government regulation of hydro-electric power, international disarmament, and the future of the American jury system. He eventually served as president of the debate club, known as the Quibbler’s Forum.

Aside from debate, Fortas took an active part in other student activities and organizations. He oversaw the poetry section of the college’s literary magazine. He was inducted into both the national honorary fraternity for leadership, Omicron Delta Kappa, and the literary honor society, Sigma Upsilon, the latter of which he also served as president. In addition, he served as secretary-treasurer of Alpha Theta Phi, a scholastic honor society and forerunner to the college’s Phi Beta Kappa chapter.

Most interestingly, Fortas joined about a dozen and a half students and a handful of faculty members as part of a campus philosophical club known as the Nitists. “Each member,” according to the yearbook, “contributes a paper during the course of the school year and reads it in meeting, whereupon it is discussed by others.” According to a friend’s recollection, Fortas presented on the topic, “Is Life Worth Living?”, and concluded in the negative. For one who questioned the value of life, he certainly lived it to the fullest, never slowing down while in college.

Music also continued to be important to Fortas’s social life during his college years. He played in the Southwestern orchestra, and during his sophomore year served as its director. But apart from any formal responsibilities, he continued to play the violin for all sorts of occasions, as evident from articles in the student newspaper. In spring 1929, for example, he conducted two orchestras that provided the musical entertainment for the Men’s Pan-Hellenic Council’s “All-Greek” annual dance. That fall, he joined with a group of students who went on a local radio station to promote an upcoming football game, playing a piece on his violin as part of a program that included vocal solos and school cheers.

In college, finally, Fortas developed an activist streak that set him apart from many of his classmates. His studies in literature and politics, Bible, and philosophy no doubt prompted the young scholar to consider his own place in society as a Jew, as well as that of others—African Americans and the poor—who existed on the margins. He certainly saw himself as an outsider. During his junior year Fortas served as president of the independent, “non-fraternity club” and urged his fellow students to vote for socialist candidate Norman Thomas for president of the United States.

As president of the Nitist club, Fortas invited the leading local African American minister to speak on the Southwestern campus. Fortas later recalled that this was “the first Negro who had ever come there” and the first time he “shook hands with a Negro.” Reflecting on how his liberal racial attitudes took shape, he later mused, “It must have been sometime when I was in college, and it must have been the result of thinking or reading or something” that caused his own views to develop on the subject.

In spring 1930, Fortas graduated with honors from Southwestern and, with the help of Diehl and Hardwig Peres, secured a scholarship to law school. Having decided to pursue the law, Fortas considered Harvard and Yale, and both men did all they could to assist him. Diehl had gotten to know Fortas well during his time at the college. His academic accomplishments and musical talents, in addition to the fact that he was Jewish and younger than his peers, made Fortas stand out among the student body.

Diehl wrote strong recommendations on his behalf. Describing Fortas as “one of our first honor men,” he made clear that Fortas did not have the means to attend law school. “His people are poor,” Diehl wrote to Harvard Law School, “and he has secured his education by means of his own efforts, aided somewhat by friends who know and believe in him.” Diehl went on: “The boy really needs all the help he can get, and you would not regret bestowing a scholarship upon him. He is a young man who will be heard from, and I commend him to you for your very careful consideration.”

Peres favored Yale, and he again played a crucial role in charting young Fortas’ course. Israel Peres, the former Memphis judge, had attended Yale as both an undergraduate and law student, and Hardwig Peres wrote to Yale explaining that Fortas had been the first recipient of the Peres Scholarship at Southwestern. Playing up the rivalry between the two law schools, Peres also noted that the president of Southwestern was “corresponding with Harvard to get one of their scholarships.” Peres continued, “[B]ut of course I would prefer Yale.” At the same time, Peres wrote to his friend Diehl, asking him to write a recommendation to Yale, a request with which Diehl happily complied.

After he left Memphis for New Haven and eventually Washington, D.C., Memphis and Southwestern continued to tug at Fortas, as he remained in close touch with both Diehl and Peres. In their correspondence in the years after Fortas’s graduation from Southwestern, Diehl consoled his young protégé after Woolf Fortas’s death from lung cancer and confided in the successful alumnus about some of the college’s financial problems. At the same time, Peres wrote letters on Fortas’s behalf for various positions in government and counseled him in the midst of a minor public scandal about Fortas’s draft status during World War II.

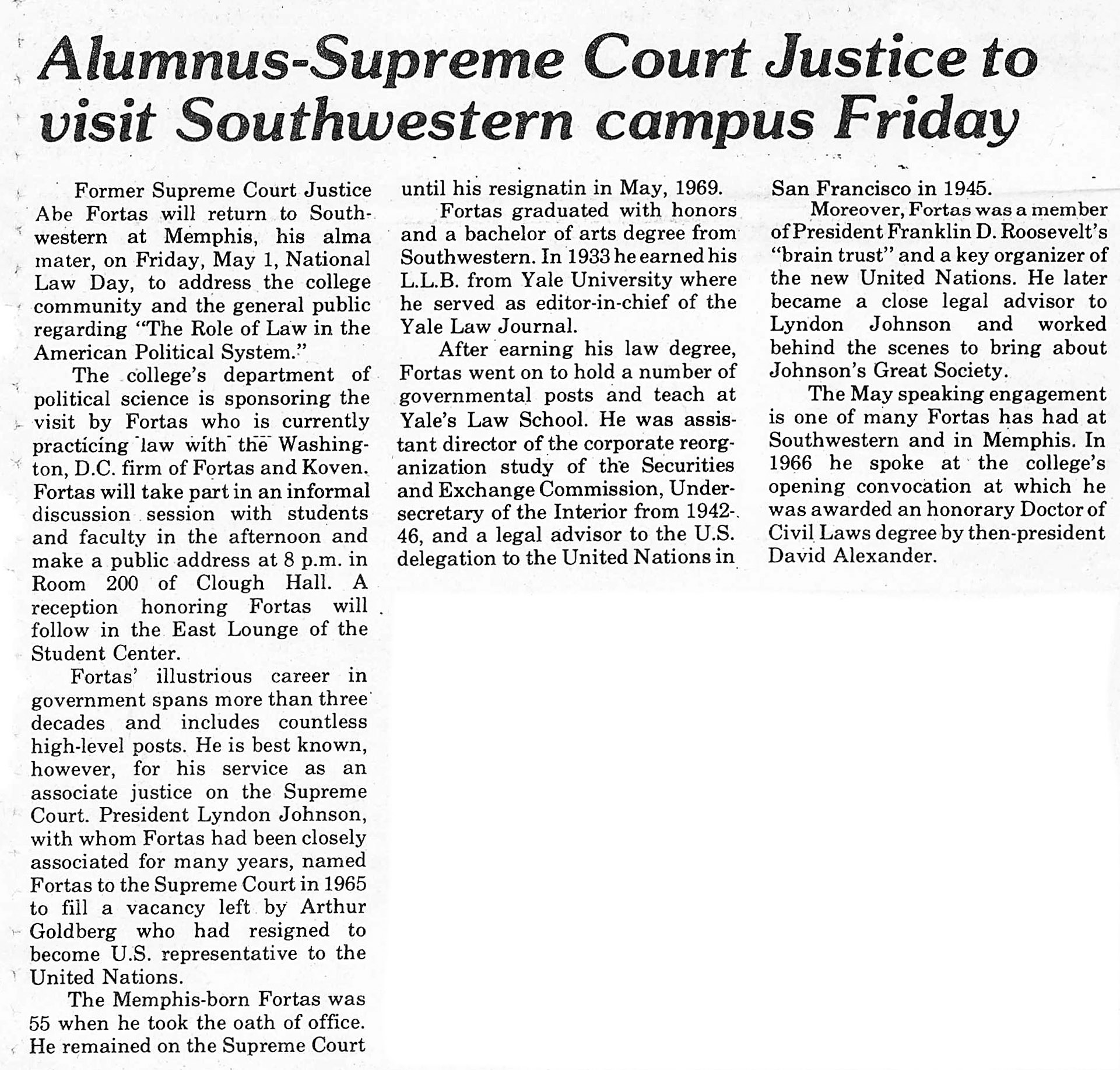

In 1946, Diehl invited Fortas to return to Memphis to deliver the Alumni Day Address during the commencement celebration, the first of several appearances that he made at the college. By that time a veteran of New Deal Washington, Fortas had recently left a position at the Interior Department to start a D.C. law firm. The largest Alumni Day crowd in the college’s 98-year history attended the event, and the audience included Fortas’s family members, as well as Diehl and Peres.

In his 1946 speech, Fortas urged his white southern audience to rethink their commitment to racial segregation. “It seems to me that our domestic problem and specifically the problem of the South must also be dealt with positively,” he stated. “…We must not fall into the trap of assuming that what is must be divinely right and must at all costs be protected from change.” He continued: “We must realize that in this country of ours the democratic and constitutional promises of opportunity for liberty and the pursuit of happiness are not the exclusive possession of a few. They are the rights of all.” It would be another 18 years before the first African American students would enroll at Southwestern, and Memphis remained a deeply segregated city, but in his speech, Fortas offered a bold vision for the future of the college and the country.

Commitment to an expansive vision of constitutional liberty became one of the hallmarks of his subsequent career as a lawyer and a justice. In 1963, he argued Clarence Earl Gideon’s case before the U.S. Supreme Court, which culminated in the Court’s famous decision in Gideon v. Wainwright affirming the Sixth Amendment right to counsel in all capital cases.

After President Lyndon Johnson appointed him to the Court, Fortas wrote landmark opinions extending due process protections to juvenile offenders in In re Gault in 1967 and insisting on the free speech rights of antiwar high school students in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District in 1969. He wrote another landmark opinion upholding the rights of religious minorities, Epperson v. Arkansas (1968), where the justices struck down a state antievolution statute as a violation of the First Amendment. In a host of other cases, he joined the Warren Court’s liberal majority in carrying out the revolution in constitutional rights that was occurring during the 1960s.

Unfortunately and perhaps unjustifiably, Fortas is perhaps best known for his downfall. After Johnson nominated him for the position of chief justice in June 1968, Senators questioned the appropriateness of his close personal relationship to the President, as well as his acceptance of an honorarium raised by friends and clients for his teaching a course at American University. Senate opposition prompted Johnson, who by that time had announced he was not running for re-election, to withdraw the nomination for the chief justiceship. Nearly a year later, Life magazine reported that Fortas had received a sizable honorarium for serving as a consultant to a charitable foundation, a financial relationship that many viewed as unethical. After months of controversy, Fortas resigned his seat on the Court in May 1969.

Whatever the shortcomings typically associated with him, Fortas was an idealistic Justice who possessed a distinctive moral vision for society. Born and raised in humble circumstances, Fortas’s college experience transformed his life. While at Southwestern, Fortas seized on opportunities afforded by an education in the liberal arts tradition and benefitted from mentors who took a deep interest in his future. His years on campus opened up to him the world of ideas, instilled in him a deep sense of justice, and set him on a path toward public service. He went, in essence, from Southwestern to the Supreme Court.

Dr. Timothy S. Huebner, the Irma O. Sternberg Professor of History, serves as the associate editor of the Journal of Supreme Court History, published three times a year by the Supreme Court Historical Society in Washington, D.C. This piece is taken from his recent article, “Memphis and the Making of Justice Fortas,” Journal of Supreme Court History, 42 (2017), 314-336.