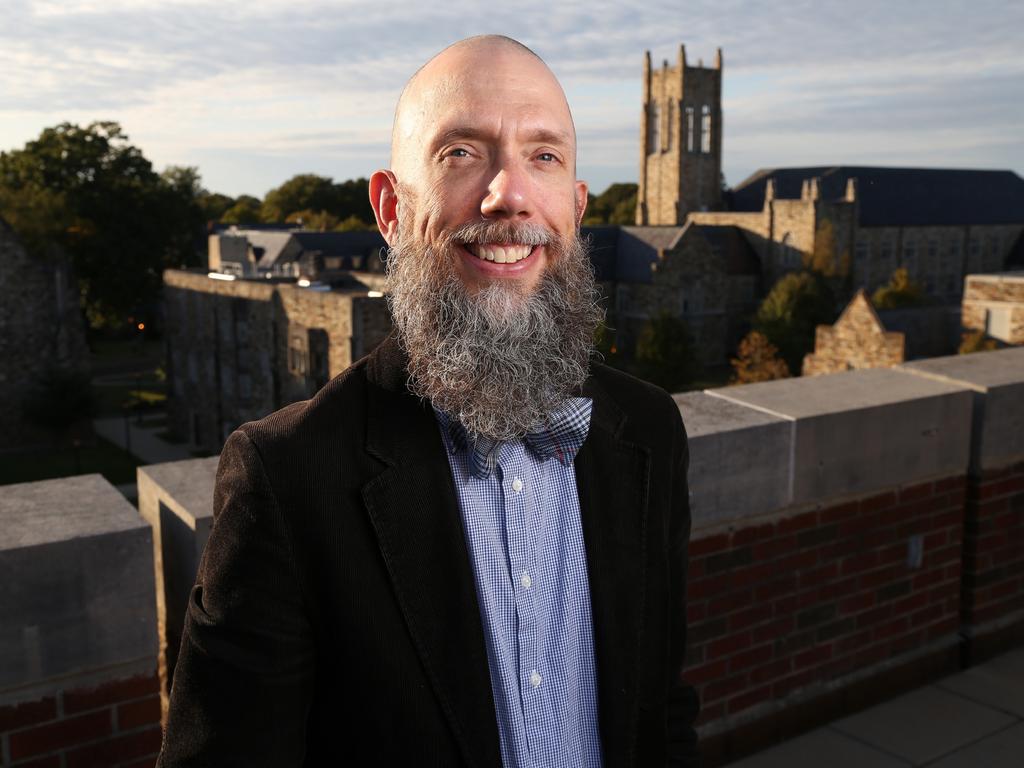

Physics professors Dr. David Rupke of Rhodes College and Dr. Alison Coil of the University of California San Diego, along with a group of collaborators from around the world, have had a breakthrough in understanding a key process in galaxy evolution.

They report first-time evidence of the role galactic winds—ejections of gas from a galaxy—play in creating the circumgalactic medium (CGM), a reservoir of gas that exists in the regions around a galaxy. Most of the visible matter in the universe actually lies around and between galaxies, and the CGM is important because of the role it plays in star formation and cosmic evolution. Rupke and Coil have been studying a giant outflow of gas surrounding the galaxy known as Makani, and their findings will be published in the Oct. 31, 2019 issue of Nature.

Rupke noticed that the hourglass shape of Makani’s nebula is strongly reminiscent of similar galactic winds in other galaxies, but that Makani’s wind is much larger than in other observed galaxies. “This means that we can confirm it’s actually moving gas from the galaxy into the circumgalactic regions around it, as well as sweeping up more gas from its surroundings as it moves out,” he says. “And it’s moving a lot of it—at least one to 10 percent of the visible mass of the entire galaxy—at very high speeds, thousands of kilometers per second.”

Rupke also noted that while astronomers are converging on the idea that galactic winds are important for feeding the CGM, most of the evidence has come from theoretical models that don’t encompass the entire galaxy. “Here we have the whole spatial picture for one galaxy, which is a remarkable illustration. Makani’s existence provides one of the first direct windows into how a galaxy contributes to the ongoing formation and chemical enrichment of its CGM.”

For decades, scientists have been puzzled by gases surrounding galaxies because the gases have been either too diffuse or at a temperature that makes the gas hard to see. In studying the unique composition of Makani, the Rupke and Coil team used data collected from the W.M. Keck Observatory’s new Keck Cosmic Web Imager, an instrument that is revolutionizing the ability of astrophysicists to detect faint gas. As a result, they were able to observe the huge outflow of gas extending far beyond Makani, which is a first for researchers.

These data were combined with images from the Hubble Space Telescope and the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA). From the Hubble Space Telescope, the Rupke and Coil team procured images of Makani’s stars, which showed it to be a massive, compact galaxy formed from a merger of two once separate galaxies. From ALMA, they could see that the gas outflow contained molecules as well as atoms. The data sets indicated that with a mixed population of old, middle-aged, and young stars, the galaxy might also contain a dust-obscured, accreting supermassive black hole. The wind is likely powered by stars, and a detailed comparison of the stellar ages with the wind properties suggests to the scientists that Makani is consistent with theoretical models of galactic winds.

“Makani is not a typical galaxy,” notes Coil. “It’s what’s known as a late-stage major merger—two recently combined similarly massive galaxies, which came together because of the gravitational pull each felt from the other as they drew nearer. Galaxy mergers often lead to starburst events, when a substantial amount of gas present in the merging galaxies is compressed, resulting in a burst of new star births. Those new stars, in the case of Makani, likely caused the huge outflows—either in stellar winds or at the end of their lives when they exploded as supernovae.”

This study by the Rupke and Coil team was supported by the J. Lester Crain, Jr. Professorship in Physics, Rhodes College, the National Science Foundation, NASA, and the Royal Society.

Related Articles:

“The Making of Makani” by Dr. David Rupke

“How We Discovered A Glowing Galactic Ghoul” by Dr. James Geach