By Dr. Charles Hughes

In a crowded room in West Germany, a young Army private named Elvis Presley interrupted an international press conference to say hello to one of the few women in the room. With the eyes of the world upon him, Presley approached an information officer named Air Force Captain Marion Keisker MacInnes, embraced her warmly, and thanked her for helping him to become a worldwide musical icon. Presley told the astonished room that she was the entire reason why the press conference was happening in the first place. As she later told Peter Guralnick, who related the story in his award-winning Presley biography, the moment had special and painful significance. “That was the first and only time that Elvis indicated publicly that he recognized the role that I had played.”

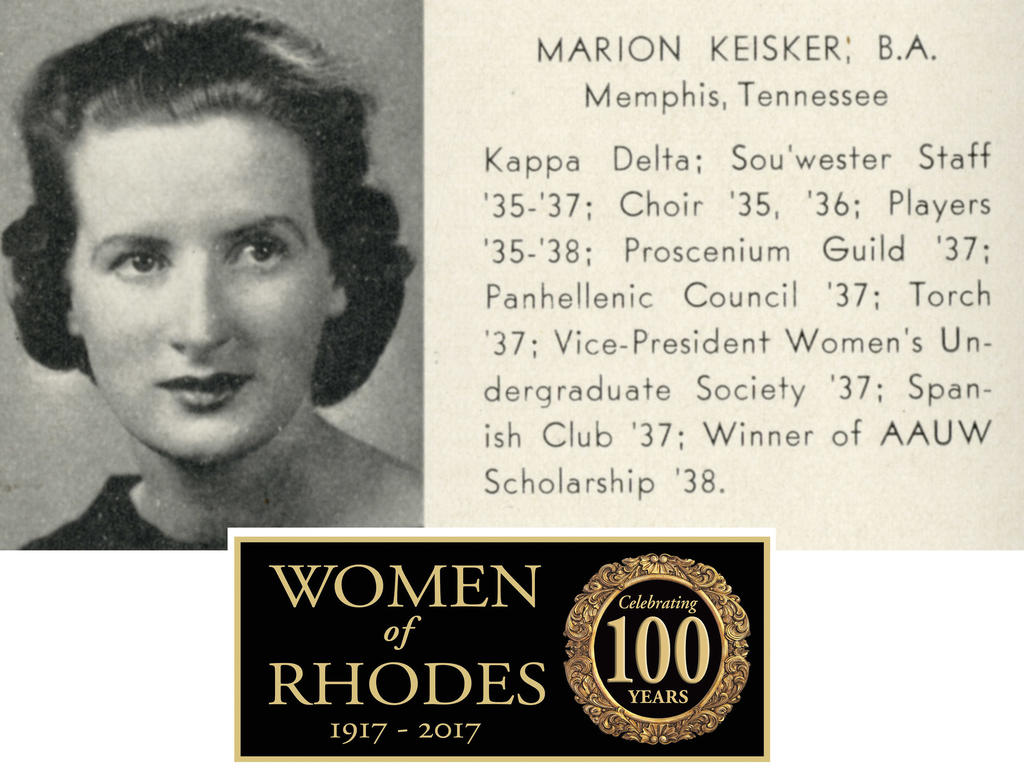

The story of this encounter captures the central yet under appreciated life of Marion Keisker, Southwestern alumna of 1942. A hidden icon of the birth of rock‘n’ roll, whose fascinating career goes far beyond Elvis Presley, Marion Keisker’s legacy reminds us not only of the pivotal role that Southwestern and Rhodes graduates have played in the history of Memphis and the United States, but also of the critical and often forgotten role that the college’s women have played in shaping our past and present.

Born in 1917, Keisker grew up in Memphis. She made her radio debut early, appearing on WREC children’s show Wynken, Blynken & Nod when she was only 11 years old. Attending Southwestern College from 1938-1942, she studied English and Medieval French and became an active participant in a variety of campus activities. She served as the vice-president of the Women’s Undergraduate Association, maintained membership in the Women’s Panhellenic Council and Southwestern Players, and served as both reporter and features editor for the Sou’wester. Her stellar campus record led her to be recognized during her senior year by The Torch Society, a national organization “formed to recognize women students who have attained a high standard of leadership on the campus.” Upon graduation, Keisker briefly lived in Peoria, IL, before moving back to Memphis and starting a career in radio.

Over the next several years, Keisker became a key player in the Memphis radio landscape. “She was probably the best-known female radio personality in the city,” Peter Guralnick noted, “at one point working on virtually every station in town, running from one to the other all day long to do advertising spots and popular quiz-show, dramatic and comedy programs.” Hired full-time at WREC, she hosted the city’s first talk show directed towards women, “Meet Kitty Kelley,” where she fielded questions and dispensed advice, as well as the weekly “Treasury Bandstand” broadcasts from the Peabody Hotel, where local big bands performed the pop and jazz hits of the day. It was during these shows that Keisker met the show’s engineer Sam Phillips, an ambitious Alabama transplant with plans to open a recording studio. Sensing Keisker’s interest and expertise, Phillips asked her to join the fledgling Memphis Recording Service – soon renamed Sun Records – as studio manager.

To this day, Marion Keisker is still usually presented in the Sun Records story as merely an assistant or helpmeet to Sam Phillips. But she helped guide every aspect of its creative and commercial direction as it developed in the early 1950s. She even helped select the location at 706 Union Avenue and helped re-construct the building as a recording studio. “With many difficulties, we got the place, we raised the money, and between us we did everything,” she remembered later. She kept the business records and organized the distribution strategy. She “handled much of the day-to-day contact with distributors and pressing plants,” described Sun historian Colin Escott, and “nurtured the distribution network and radio contacts that would serve as a launching pad for Sun Records.”

Also, although she did not originally share Phillips’s love for R&B and blues, Keisker learned enough about the new sounds to help scout talent and arrange the musicians for sessions. (She developed a particular love for the growling blues of Howlin’ Wolf.) When a young electrician named Elvis Presley arrived in the studio in early 1954, Keisker recognized that the young man who “didn’t sound like nobody” possessed a unique talent and could fit into the emergent Sun Records musical strategy of genre-blending southern music. Even as Sam Phillips grew weary of Presley as his early recordings failed to catch fire, Keisker continued to encourage the young singer to bring more material to Sun and insisted that Phillips follow through on his idea to pair Presley with local country musicians Scotty Moore and Bill Black.

As Presley’s star rose, Keisker played a pivotal role in helping to market and promote the young singer and the musical vision he represented. Using the skills she developed at Southwestern and her work in Memphis radio, Keisker was a critical second-in-command for Phillips. In a pivotal Memphis Press-Scimitar article in 1955, Keisker even played a crucial role in building Presley’s legendary image. Keisker arranged the article through her connections with writer Robert Johnson ’35, a fellow Southwestern alum. The young singer was reticent to answer questions beyond a simple “yes” or “no,” so it was Keisker who provided most of the information. “The odd thing is that both sides seem to be equally popular on popular, folk and race programs,” she told Johnson. “This boy has something that seems to appeal to everybody.” Referring to Presley as a “hillbilly cat,” Keisker signaled the genre-crossing appeal that made Presley (and rock ‘n’ roll) a musical and cultural phenomenon. While Phillips had repeatedly told Keisker that he wanted to find a “white man with the Negro feel,” Keisker translated this vague desire into a concrete strategy.

Phillips so trusted Keisker’s instincts and experiences that he chose her to lead his pioneering all-female radio station WHER, which opened in 1955. Keisker’s extensive experience in radio made her a perfect manager for WHER, which boasted the nation’s first all-female roster and became a celebrated (and imitated) entry on America’s expanding radio landscape. Unfortunately, Keisker soon left WHER and Phillips’s employ. Noting later that she tired of the producer’s unreasonable professional and personal demands on her, Keisker left Memphis and joined the Air Force in 1967.

In the military, Keisker continued to work in communications. In West Germany, she worked at the Air Force’s television station (which is why she was in the room for Private Presley’s press conference). Upon her return to the United States, she worked in the Office of Information. After 14 years of service, Keisker retired and returned to Memphis.

Almost every telling of the Marion Keisker story begins and ends with Elvis Presley, literally and figuratively. Even in those accounts that consider her broader work at Sun Records and Memphis radio, Keisker’s life story seemingly ends when she began her military service or when she encountered Elvis in Germany. But her next chapter revealed that – after helping to change the world through Memphis music – Marion Keisker worked to make that world a better place through political activism. Upon her return to Memphis, Keisker took an active role in the burgeoning feminist movement. She became a co-founder and early president of the city’s chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW). Like its counterparts across the country, Memphis’ NOW branch advocated for women’s rights to access, equality, and protection.

One particularly prominent campaign brought President Keisker back to her old college neighborhood. In 1974, under her leadership, NOW staged anti-rape “Take Back the Night” protests around Overton Park. As historian Stephanie Gilmore noted in her chronicle of the organization, “this action exemplified their commitment to radical feminist tactics and the philosophy that linked rape to the commodification of women.” In some way, Keisker’s pivotal role in building Memphis’s feminist movement seems to be a divergence from her earlier career. But her involvement in advocating for women’s equality and opportunity seems very much reflective of a career in which her brilliance was both critical to the larger success of Memphis’ most famous cultural export, and left underappreciated in a society that still fails to fully recognize her talents.

To this day, Marion Keisker’s legacy as a critical participant in the development of Memphis music and culture has been minimized or ignored. Although writers like Peter Guralnick have added her experiences back to the historical record, she is too often presented simply as a helpmeet to Sam Phillips rather than an important collaborator. And the rich parts of her biography that do not directly relate to Sun Records – from her acclaimed time at Southwestern and her radio work to her military service and feminist activism – has been almost entirely ignored.

As we celebrate 100 years of women at Rhodes, the story of Marion Keisker is a reminder of the need to honor the women of the past and celebrate those who are transforming our future. Although Marion Keisker is not here to witness it, she surely would cheer us on.