The Remarkable Life and Career of Lawrence Anthony

By Michael Finger

An energetic group of men and women have gathered outside the Catherine Burrow Refectory at Rhodes College. They carry books, backpacks, and briefcases. A young fellow riding a skateboard dodges another student on a bike, while a kid points a camera towards Southwestern Hall and another tosses a Frisbee. An unusually tall man wearing a cowboy hat pushes through the crowd, as dogs scamper beneath everyone.

Standing to one side, a burly security guard pulls out a notepad.

If he’s writing a ticket for loitering, he has a good reason, because these figures haven’t moved an inch in more than four decades. With their elongated arms and legs, and curiously distorted faces, they form a sculpture called Campus Life, designed by Lawrence “Lon” Anthony, the longtime artist-in-residence at Rhodes College, back when it was called Southwestern at Memphis.

The name of the piece, constructed of hammered copper and cast bronze, is appropriate. Not only does it convey the range of people (and creatures) anyone might find at the school, but Anthony recruited many students to bring his creation to life on the campus.

“My entire class helped with that project for two semesters,” says Anthony, now retired and living with his wife, Anne, in the Florida Keys. “I designed the work, and my class was purposely involved as my assistants in the making of it as part of their learning experience — from how a piece is conceptualized, to the physical effort itself, to the willingness to destroy and rebuild, letting go and redoing it, all this over a long period of time.”

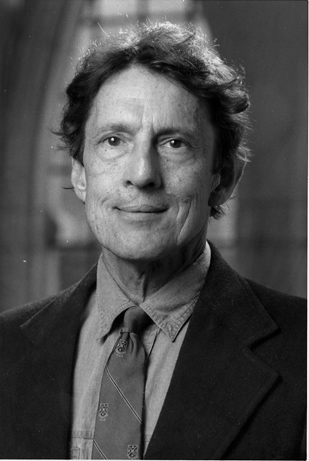

In 1996, towards the end of Anthony’s last year at Rhodes, the school hosted a retrospective that saluted his 35-year career here. For the catalog that accompanied that exhibition, Dr. David McCarthy, then (and now) the chairman of the art department, notes the significance of Campus Life: “As is typical of so much of his work, the sculpture documents the look and sensibility of its time, while also celebrating the human community as a dynamic, charming, ever-changing, and inclusive structure.”

That word “community” comes up in any discussion with Anthony’s former colleagues and students. He helped establish a thriving art community at Rhodes, by hiring teachers and expanding the fledgling department.

“From his arrival on campus in 1961 until his retirement, he was a central presence in our collective life,” McCarthy continues. “He remained unflagging in his commitment to integrating the study of art with the broader curriculum of the college, while also insisting that the production and study of art was an all-consuming passion.”

During those early years Anthony taught every class in art history, painting, and sculpture the school offered. Students remember him fondly as a guide, teacher, mentor, friend, and inspiration. They describe the “master and apprentice” bond he formed with them, and many give him credit for where they are today, whether they are professional artists or working in other careers. Some say, quite emphatically, that Rhodes wouldn’t even have an art department, if not for Anthony.

McCarthy joined the faculty as an art historian in 1991, after meeting Anthony at a national conference. “When I was hired,” says McCarthy today, “the art department that I walked into was very much Lon’s art department. He built it.”

The Long Journey to Memphis

Born in 1934, Lawrence Anthony grew up on a farm outside Florence, South Carolina. As a child, he displayed artistic talent, but his family was too poor to provide him with the means of expressing it. So he resorted to drawing on scraps of paper and cardboard, or using a fireplace poker to whittle designs in the fireplace mantle. The Anthony family somehow managed to subscribe to the Book of the Month Club, and Anthony admits that he made some of his earliest drawings in the blank pages of those books. “My father never had time to read them,” he says, “and my mother didn’t object.”

Anthony served as editor of his high school newspaper. He enrolled at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia, “because I thought I wanted to be a newspaper reporter.” All along, however, he had been sketching and drawing on anything he could find, even pieces of shirt cardboard, so he decided to major in art. There was just one problem. Washington and Lee didn’t offer an art degree; this was in the 1950s, and few major colleges did.

One day, however, he sat down with a sympathetic dean, who “wrote out all the courses he could think of that had anything to do with art,” he says. “So I got a degree, but I didn’t really major in anything — just kind of a conglomeration of stuff.”

In the early 1950s, the U.S. was involved in the Korean War, so Anthony joined the Navy Reserves. He enrolled in Officer Candidate School and was transferred to Pensacola, but a history of asthma cut short his plans to be a pilot. Instead, he spent his time on various ships “as the lowest of the low, mostly scrubbing decks and chipping paint off them.”

He was relocated to different Navy yards up and down the East Coast, and when the war finally wound down, Anthony’s military stint came to an end. He journeyed to Europe, where he spent a year visiting galleries and museums there. That was a formative experience, and when he returned to the United States, he decided, “I’d better get on with my art.”

So, in the late 1950s, Anthony enrolled at the University of Georgia, which had one of the top art departments in the country. He was mainly interested in drawing and painting and remembers his first meeting with a professor there. “I didn’t even know how to stretch a canvas,” he says, “so my whole portfolio was things I had painted on cardboard.” Even so, that professor liked what he saw, admitted him to the department, and two years later Anthony earned a master’s from UGA.

Along the way, however, he mingled with other students who were focusing on sculpture and discovered he had a knack for it. As he explains, “It was just something I started doing on the side, but it was more interesting than painting. I discovered I could deal directly with images and not do all this push-and-pull with the paint surface.”

What’s more, he encountered professor Leonard DeLonga, a talented metal sculptor. “He was highly important and influential to me,” Anthony says. “A lot of it was his personality. He worked on his art, and we watched him, and he let us do whatever we wanted to do. It was a good experience, and that’s how I ended up doing sculpture.”

The University of Georgia had good connections with other schools, so when Anthony approached graduation, “they had found two jobs for me. One was the Dayton Art Institute in Ohio, and I was really interested in that because it was a straight-up art school.”

The other job offer came from Southwestern at Memphis.

“This was 1961, and the dean who interviewed me was Jameson Jones ’36,” he says. “He drove me all over town, to Beale Street and Downtown — the whole scene was really hopping back then — so I took the job here.”

Anthony was hired as the artist-in-residence and assistant professor — for a department that didn’t really exist. Yearbooks from that period sometimes devote a single page to the fine arts department, featuring just two faculty members. Professor Ray Hill taught drama classes, and Assistant Professor Lawrence Anthony taught art. That was it.

Even more astonishing, compared to the facilities at Rhodes today, was the location of that art department. The school had acquired five wooden barracks, surplus buildings from the U.S. Army, and lined them up in an open field in the northeast corner of the campus. The “Art Shack,” as it was called, was home to the Southwestern art department. Anthony remembers the other crude structures held English, history, psychology, and sociology classes. “You could hear everything that was going on in the other buildings,” he says, “and with just one heater for the whole building, it was always drafty and freezing cold.”

Anthony would join other faculty members and drive to an Army surplus store in Nashville and, often with his own money, buy much-needed supplies. “There would be tons of equipment, some of it from the Korean War, or World War II. It was like Christmas, and I pretty much built the art department from scrap.” He also recruited skilled teachers from the Memphis College of Art, such as Burton Callicott and Mary Sims, to teach part-time.

During this period, Lon met Anne Sayle ’73. After finishing college, she took a job teaching grades 1-3 at a little school in Dundee, Mississippi. She and Anthony were married in 1976. While Lon spent his days at the college, Anne taught at other schools in Memphis, ultimately teaching art at St. Mary’s. Also an accomplished sculptor, she was a singer, songwriter, and composer.

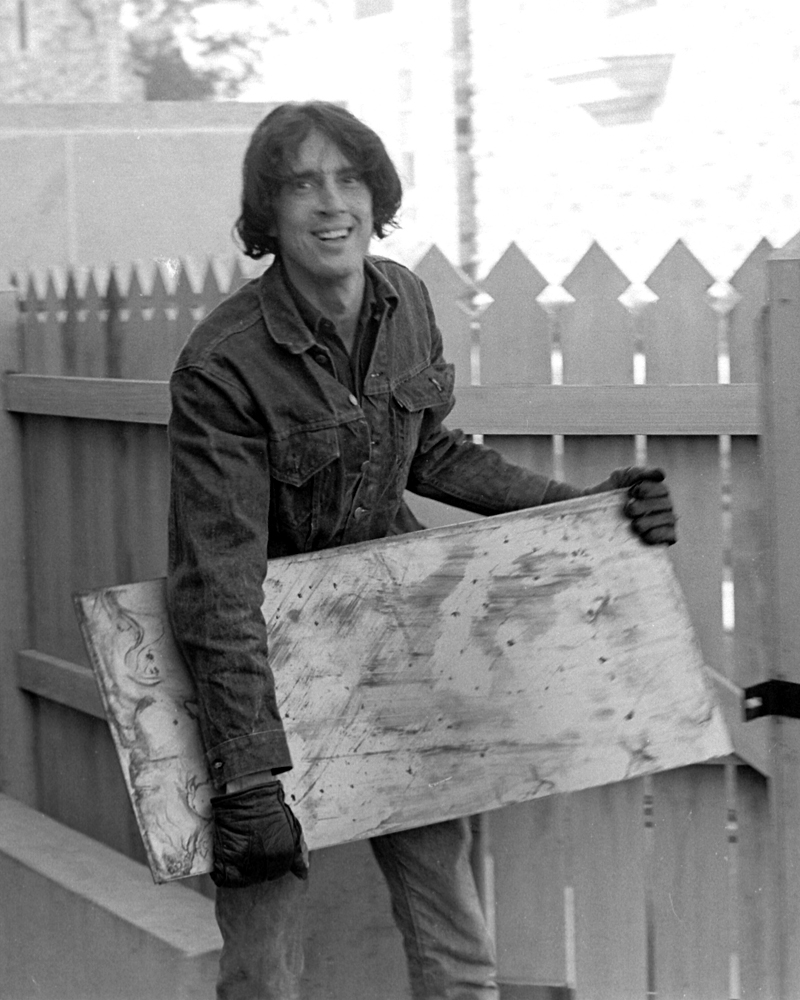

Anthony was a distinctive figure on campus, with his long hair and penchant for turtlenecks and denim jackets. He didn’t like cars, so he walked or rode his bicycle everywhere. He bought a bungalow on Washington Avenue, a block west of Cooper, which he and Anne transformed into a home, studio, and off-campus hangout for students and teachers.

The house was just across Overton Park from the school, and “I really loved that,” he says. “I was always close to the students, and a lot of the faculty lived like that in those days. Nobody back then drove 20 miles to come to work. It was a wonderful environment, and the community in Midtown was my world.”

Master and Apprentices

“First and foremost, Rhodes College is a community,” says David McCarthy. “That community developed because people take the lead in nurturing and sustaining them, and that’s what Lon did. He had an acute sense of how important the arts were, and how much students needed nurturing. And sometimes that meant just somebody standing over your shoulder, saying, ‘This is important’ and ‘You can do this.’ His approach to teaching was not so much telling students what to do, but showing them how to do it. He became more of a sounding board, than a person assigning tasks. That’s a refrain you hear from a lot of his students.”

One of those former students is Jim Watson ’77, a Rhodes graduate now working as a mechanical engineer in Kalispell, Montana. Watson majored in philosophy, but says, “I probably ended up with as many hours in sculpture as I did in philosophy.” He gives Anthony credit for that. “I always liked making things, and I’ve always been creative, and Lon provided me that opportunity,” he says. “He allowed me in the studio as if I was one of his full-time art students.”

When Anthony began work on the Campus Life sculpture, Watson became one of his student apprentices. “I grew up on a farm and knew how to weld and do metalwork, so I ended up kind of the number-two guy under him on that,” he says. “A lot of students were involved. They would hammer out the copper pieces and I would assemble them under Lon’s direction.”

Watson says Anthony had an “amazing combination of artistic talent combined with great technical ability.” At the same time, “we all loved him because he was so approachable and personable.” In fact, he gives his former teacher credit for his current profession. “After I got out of school, I farmed in Mississippi for seven years, but then I went back to college and became a mechanical engineer. Because engineering and art and sculpture are highly related, I felt that was Lon’s influence.”

Campus Life was dedicated in 1977. Ten years later, another campus landmark was unveiled, and again Anthony played a role in its creation — and the career of the student who created it.

“Even though I was always drawing, painting, and sculpting, I never imagined that I would pursue the arts as a profession,” says Ann Moore ’88, “but meeting Lon literally changed the course of my life. He was the magi, and I became the wizard’s apprentice.”

As a freshman, Moore began majoring in biology and took a sculpture class at Rhodes. “When I poured bronze with Lon in the small foundry we had on campus,” she says, “I was captivated by the process — it was a magical transformation that I simply had to master.”

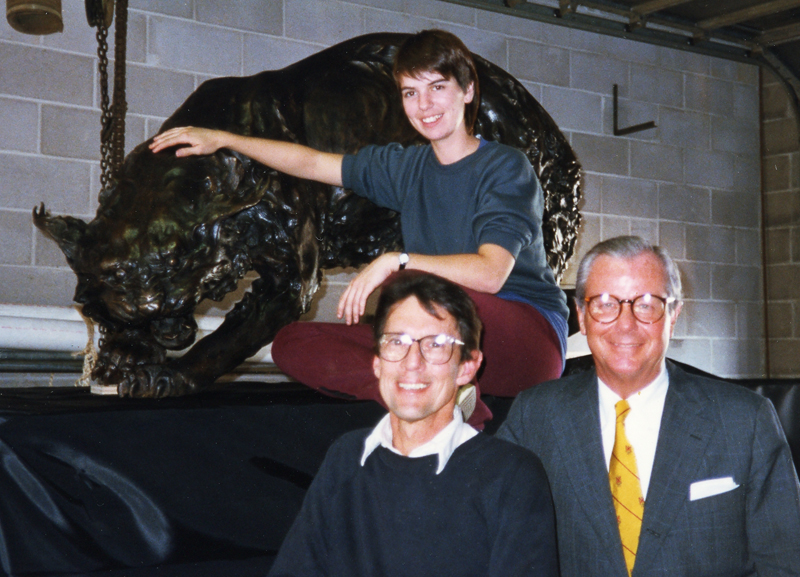

One of Moore’s classes required her to make a series of related objects. She created three small cats playing with each other, and “those cats paved the way to Lon asking me to create the monumental bronze Lynx sculpture for Rhodes.”

Anthony says the college originally asked him to create the sculpture, “but I told them I have a student who can do this a hundred times better than I can. I worked with her somewhat, but not much. She did that on her own, and it’s hers, straight up.”

Moore doesn’t quite agree with that, saying that her teacher walked her through the entire design process and gave her much-needed confidence. After all, this figure would be the symbol for the whole college. “I had doubts that I could tackle such a big project,” she says, “but Lon reassured me by saying he didn’t know how it could be done either, since he had never made a large bronze like it, but we would figure it out together.”

The project took two years, and Anthony handed Moore the keys to the studio so she could work on it at night and weekends. The unveiling of the finished piece on October 10, 1987, revealed what Moore and others have also said about another of Anthony’s traits: his quirky sense of humor. Instead of just pulling a sheet off the giant cat, Moore decided she wanted to wear a lion-tamer’s outfit.

“Lon was such a good sport about my crazy idea, and he found the costume somewhere, along with the boots, whip, and chair,” she says. “He looked so proud of my accomplishment as he drove the statue onto the field in the back of a pickup truck, with me in my red coat and top hat, and the Rhodes cheerleaders chanting a special cheer for the Lynx. I’ll never forget that surreal day, or his ear-to-ear grin that I’m sure matched mine.”

The bronze Lynx stands close to Clough Hall, the modern, spacious complex of classrooms, studios, and gallery space that opened in 1970, finally replacing the decrepit (though fondly remembered) Art Shack. Athletic fields cover the former location of those old barracks today.

After college, Moore worked for years as foreman at the Lugar Foundry in Eads. “A true mentor,” she says, “Lon opened doors for me and showed me possibilities for my life’s work that I didn’t even know existed.”

A Life in Art

Anthony worked on his own projects while helping students and friends complete theirs. One of his best-known public pieces here is the Dramatis Personae grouping that adorns the grounds of Theatre Memphis. Nine massive abstract figures, some more than eight feet tall and formed from half-inch steel plates, represent well-known actors and characters from drama: Sarah Bernhardt, Cyrano de Bergerac, Punchinello, and others.

“This was envisioned and originally installed as an interactive piece,” says Anthony. “It was like the figures were relating to each other in some way, either talking or confronting each other.” The work, which took two years to complete, was unveiled in 1983. About a year later, when Theatre Memphis expanded, the figures were separated, and they now pose individually on the front lawn, visible to anyone who drives by the complex on South Perkins.

Anthony remembers the project was, almost literally, a back-breaking task. “This was very heavy stuff, and I had to cut it all out,” he says. “Nowadays you can draw a picture, take that to a fabricator, and they’ll cut it for you. We didn’t have that back then, so I used an acetylene torch, which was messy and sloppy. But it worked.”

He created many other pieces, either as public commissions or on his own, using an astonishing variety of materials. Dramatis Personae was high-grade Corten steel plate, but other works were cut, forged, welded, cast, and carved from copper, bronze, clay, concrete, alabaster, figwood, mahogany, cedar, ceramics, plywood, polyester resin, and fiberglass. Some of his mixed-media creations incorporated different kinds of paint, embellished with odd materials such as Elmer’s Glue.

Anthony stepped down as chairman of the art department in 1991, but he continued to teach at Rhodes part-time until he retired in 1996 and left Memphis. His works are displayed in private and public collections around the world, including the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, the University of South Carolina, Vanderbilt University, the Delgado Museum of Art in New Orleans, the Virginia Art Museum in Richmond, the Metropolitan Opera Company in New York City, the Terre des Hommes Pavilion in Montreal, and the U.S. Embassy in Bern, Switzerland.

“Underpinning all his work,” writes Marina Pacini in the essay that introduced Anthony’s 1996 retrospective at Rhodes, “is a strong narrative component. That Anthony is a consummate verbal storyteller comes as no surprise. Many of his sculptures seem to have stepped right out of one of his tales.”

David McCarthy echoes that impression, saying, “Lon was very much in that Southern tradition of spinning a yarn, often about growing up and how he came into a life of art.”

At age 85, living with his wife, Anne, in a spacious beachfront house on Summerland Key in Florida, Anthony is still a storyteller today. He can regale callers and visitors with tales about his long and fascinating life, and the people he’s met along the way. Although he doesn’t travel as much as he used to, and hasn’t made a return visit to Memphis in almost 20 years, he stays connected.

“Thanks to the internet, I keep in touch with the world, and am always learning new things,” he says. “And with Facebook, I know that a lot of my students have done wonderful things.”

Indeed they have. “What Lon Anthony did for this institution was to find a way to make sure art would thrive on this campus,” says McCarthy. “He recognized his students’ creativity and talent and then provided them with the means for letting that grow.”