The college’s small RHOK-SAT satellite could have big implications for renewable energy.

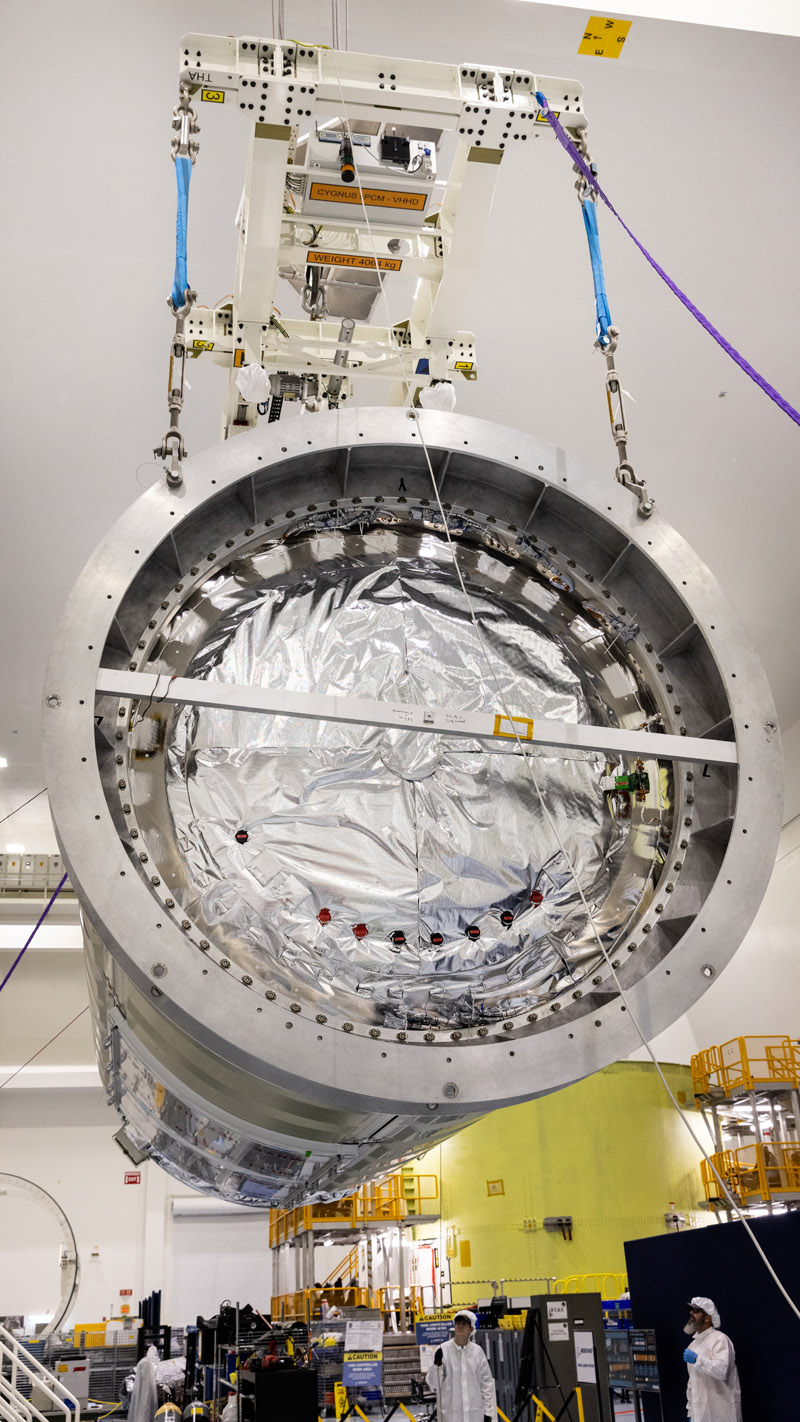

At Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, several Rhodes faculty, alumni, and students watched with bated breath as a rocket prepared for launch. If all went well, the day would mark a successful initial step for the college’s first-ever space mission. On board, a small, cube-shaped satellite six years in the making could potentially lead to new breakthroughs in renewable energy. When the rocket finally took off from the launchpad and soared out of the atmosphere towards the International Space Station (ISS), the cheers and shouts of joy rivaled the ensuing sonic boom.

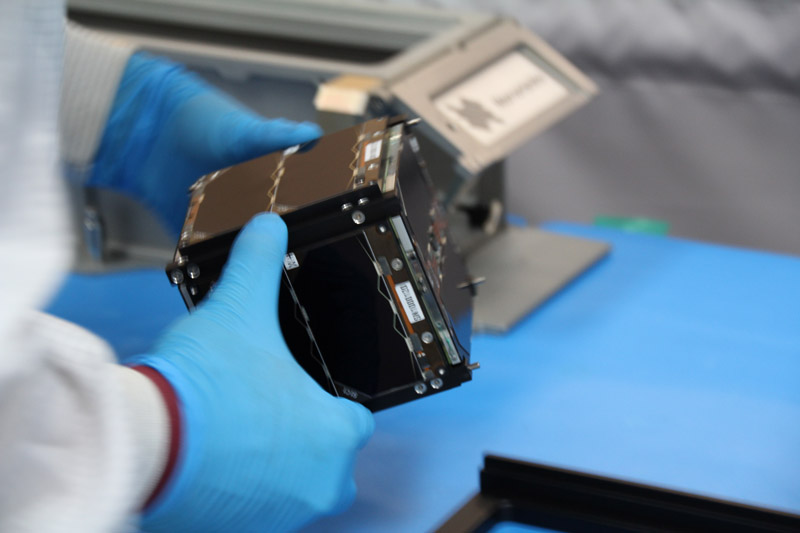

The Falcon 9 rocket carried within its cargo RHOK-SAT, a four-inch, cube-shaped satellite built entirely by Rhodes students for the purpose of testing novel solar cells in the environment of space. Its presence aboard the spacecraft meant that the satellite, the first of its kind produced by Rhodes, had received the stamp of approval from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and could officially embark on its scientific mission.

The road to that moment of triumph was a long one, filled with myriad challenges ranging from satellite construction to international technology partnerships and even to HAM radio certification and licensing with the FCC. But it’s a road that every contributor embraced from day one, when Board of Trustees member Dr. Charles W. Robertson, Jr. ’65 reached out to Rhodes with a proposal. Robertson, the founder of NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., has long been a staunch supporter of the sciences at Rhodes, providing financial support and his expertise for fellowships, projects, endowments, and facilities such as Robertson Hall, named for his parents. He’d had his eye on NASA’s CubeSat Launch Initiative (CSLI), a program that provides U.S. universities, high schools, and nonprofit organizations the opportunity to build and fly their own miniature satellites aboard a NASA-sponsored rocket. If Rhodes applied to the program, he would be willing to provide funding for the project.

“I’d been watching other CubeSat projects, and it really looked like something that could get students really fired up and interested,” says Robertson. “I brought this to [professor of physics] Brent Hoffmeister P’25 in 2019, and we agreed Rhodes would be an excellent environment to take on a project such as this.”

But building the satellite was only one step; the proposal also required a scientific mission. In January 2020, professor of physics and department chair Ann Viano P’25 attended a conference where she began discussions with researchers from the Photovoltaic Materials and Devices Group, led by Dr. Ian Sellers of the University of Oklahoma (OU) (now at the University of Buffalo), about testing the behavior of perovskite photovoltaic cells in space. The group had expertise in characterizing cells but no way to check their performance in space. Together, Rhodes and OU could solve that problem. “If perovskite cells remain hardy in space,” says Viano, “they show great promise for long-duration missions far from the sun due to their high efficiency in converting light to electrical energy."

Hoffmeister authored the proposal in 2020 in collaboration with other Rhodes faculty and Sellers’ team at OU, and it was officially accepted by NASA in 2021. Rhodes would build and produce the satellite, while OU provided a solar cell. Rhodes also looped in the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden, CO, to produce more cells. Work on the satellite, nicknamed RHOK-SAT due to the collaborative effort between Rhodes and OU, could begin.

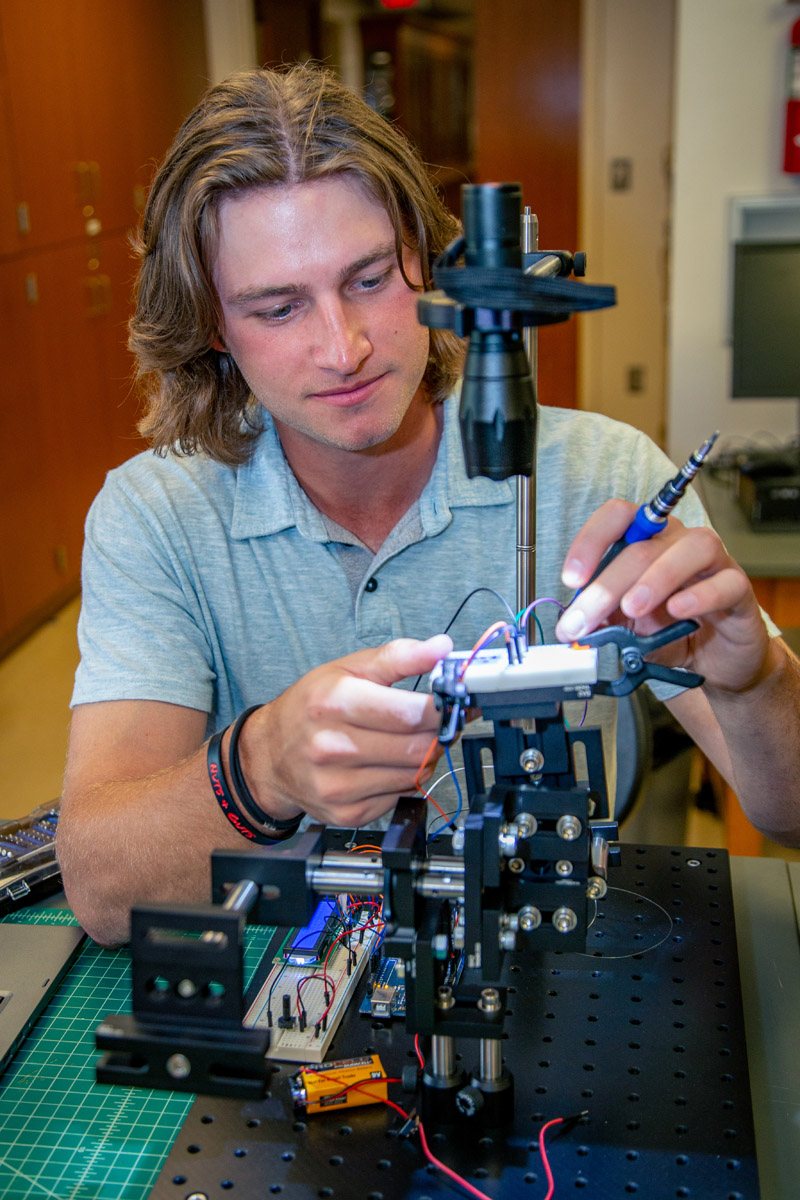

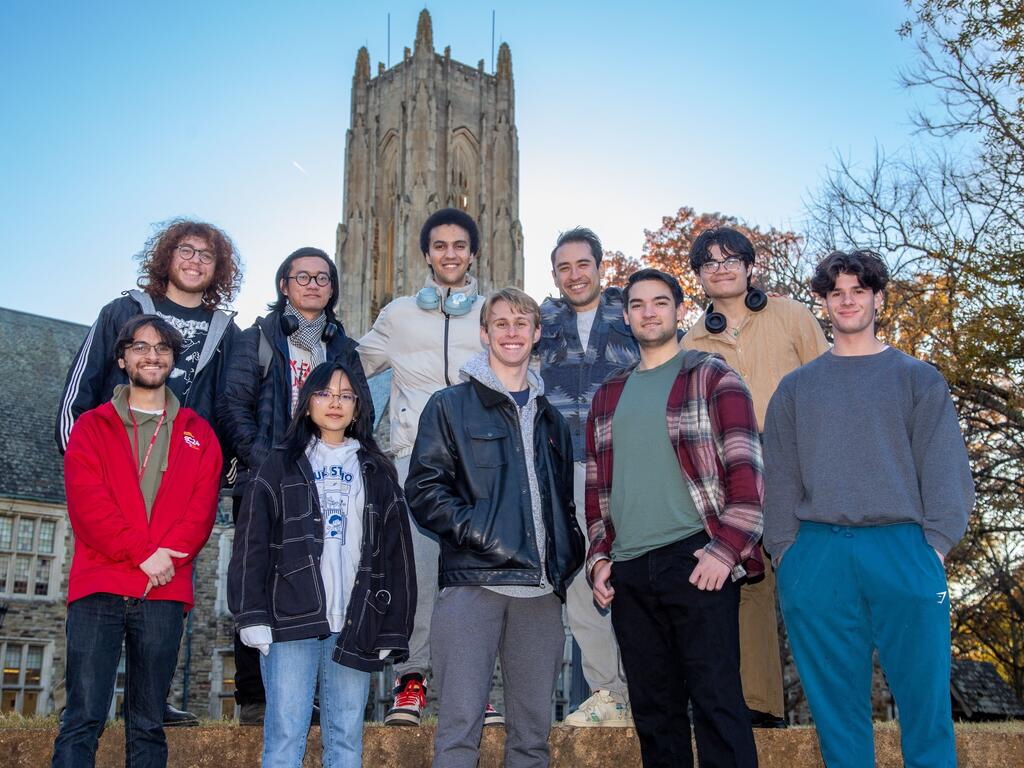

Throughout the process, the Rhodes team was mentored by physics professors Bentley Burnham (who replaced professor Joseph McPherson after his departure from the college), Hoffmeister, and Viano, and mathematics and computer science professor Phil Kirlin. Students from those two departments, and others, have all contributed to the design of RHOK-SAT. While much of the background work proved bureaucratic in nature—Burnham frequently found himself on the phone with ISISPACE, a satellite solutions company in the Netherlands that manufactured various components required for the CubeSat model—the CSLI program is primarily educational in nature, and the faculty mentors stress that the students led the entire project themselves.

“Our focus was mainly on making sure students had the resources they needed to complete the work,” says Viano. “Students have done everything in this project: They’ve handled computer-aided design, fabrication of test pieces and actual space hardware, electrical design, solar cell science, creation of flight and communications software. There is no class or set of classes that can give this extensive experience and foster a truer sense of teamwork for a common goal.”

Up to launch and beyond, there have been a lot of eyes on the project. The perovskite solar cells are layered thin-film materials with chemical compositions and atomic structures in the layers that lead to high output power when in sunlight. The name perovskite refers to the specific crystal structure in these thin-film layers, and the material has increased in solar efficiency in recent years. If successful, RHOK-SAT could showcase these cells as a viable new energy source for long-range space missions. “Our project is generating quite a bit of interest because there’s a lot of money behind developing this technology,” says Hoffmeister. “A lot of big players in the aerospace industry want to know how viable this is, but there really hasn’t been much research into it. So, they’ve been watching closely to see what we might find out.”

Jose Pastrana ’20 was introduced to the project shortly before graduating, but the nature of the work, and the excitement of building something to go into orbit, convinced him to stay involved in the project. Around his full-time job as an engineering manager at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Pastrana acted as lead engineer of the CubeSat program at Rhodes to liaise between the physics and computer science components of the project to make sure everything ran smoothly.

There have been plenty of moving pieces to maintain. In addition to constructing the satellite—putting together the durable shell, designing circuit boards and electrical components, and many other small implements—students also worked on software that ensured the satellite could consistently communicate with a ground station once it was in orbit.

“Students had to write all the software that keeps the satellite running while it’s up there,” says Kirlin, “which is much more challenging when the software is running on a computer up in space that you don’t have physical access to. That’s things like keeping the battery running, keeping the solar cells oriented towards the sun, handling any anomalous circumstances that might arise.

“That software is also running and managing the scientific experiment,” he adds. “That’s data collection from the cells and sending it back to the ground station when the satellite is over either our ground station or one of the others around the planet we can tap into.”

When RHOK-SAT orbits above Rhodes, it will speak to a radio station that sits atop Rhodes Tower. The station—which includes an antenna, software-defined radio, and a microcontroller board—is part of SatNOGS, an open-source ground-station network in which users around the globe can receive satellite health data from other satellites. This means that, as RHOK-SAT continues its orbit around the globe, Rhodes can tap into other stations in the network to gather data.

Getting licensed for that communication was another matter entirely. “There was so much paperwork and licensing we had to work through,” says Pastrana. “We were interfacing with so many agencies to get this approved. We had to make sure the Federal Communications Commission approved our signal. It just goes to show how many agencies are involved in a project like this, and we learned how to effectively maneuver within that framework.”

When a dedicated frequency for RHOK-SAT proved prohibitively expensive, the team looked for other ways they could manage it. The answer came in the form of ham radio, and Rhodes filed an application with the International Amateur Radio Union. “We have a frequency to talk to the satellite, and a frequency for the satellite to talk to us,” says Burnham. The team then communicated that frequency to ISISPACE, who would tune electrical components to the appropriate frequences before shipping them to Rhodes.

Getting approval for an amateur frequency comes with the expectation of giving back to the amateur radio community; in addition to transmitting data, RHOK-SAT will be used as a “repeater” for amateur operators. “The frequences are made public,” adds Burnham, “so operators can talk to a buddy across the globe by bouncing it off our satellite.”

The lead-up to launch day was a nervous one for the Rhodes CubeSat team. Six years of research, labor, and painstaking craftsmanship from more than 30 students were about to come to fruition on a singular rocket launchpad in Florida. But first, the weather needed to clear up. Threats of rain and heavy cloud coverage could have indefinitely delayed the launch. But come launch day, the skies were mostly sunny. “NASA really turned the whole thing into a party,” says Burnham. “People were so excited about what was going to happen, and it was such a great experience for us to be there in person.”

RHOK-SAT was situated aboard Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus XL spacecraft, carried on the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket during a resupply mission to the International Space Station (ISS). After being pushed from the ISS on Dec. 2, it is expected to remain in orbit for about a year. Data collection will last for about nine months, and the satellite will act as a repeater until it wears down.

Viano, Hoffmeister, Burnham, and Robertson all gathered at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station to watch the launch along with Pastrana, Damian Nguyen ’25, and Kerry Tang ’27. Back on campus, Theo Akritidis ’27 hosted a CubeSat launch watch party in the Spence Wilson Room in Briggs Hall. The chance for students to live these unique experiences is why Robertson supported the project in the first place. He recalls his own trip as a student with physics professor Jack H. Taylor ’60 to Alaska in 1963 to measure a solar eclipse. “At that time, there was really no way to get good data from the corona except during an eclipse, so we mounted spectroscopy instruments on World War II gun mounts at an airfield. That was an incredible experience, one led by students. I think back to the opportunity I had to tackle a big project like that, and it’s really important that students are able to continue having these scientific projects beyond the academic environment.”

The minutes leading up to launch offered a moment of reflection for the team. “I’ve made a lot of new friends working on RHOK-SAT,” says Tang, a computer science major who contributed to both the hardware and software aspects of the project. “Since the solar cells are easy to manufacture, we’re hoping that we can see some real applications from this research. Plus, having something sent to space is a very cool thing to have done in college.”

For Nguyen, who worked on developing the payload, it was an especially sweet moment. The CubeSat project had attracted him to Rhodes from Hanoi, Vietnam. But the experience and the launch were only the first step for him. “I really wanted to get real, hands-on engineering experience and have direct experience in the aerospace industry. This was one of the biggest factors in me coming to Rhodes, so I’m happy to see it pay off.”

Some of the earlier CubeSat participants have used the project as a launching point for their own careers in the aerospace industry. Olivia Kaufman ’23 works as a satellite systems engineer at CesiumAstro, Benjamin Wilson ’22 is an engineer at AVS US, while Guiliana Hofheins ’22 is a Ph.D. candidate in aerospace engineering at Cornell University, to name but a few. “Students who have participated in the project are garnering great success in aerospace engineering,” says Viano. “It has also opened doors to summer internship opportunities in the field. Several high school students have volunteered on the project as well, and hope to matriculate to Rhodes.”

Like some of his predecessors, Nguyen plans to continue working in the aerospace field. “After graduation, I became the technical lead of the continued CubeSat project in the physics department, and we hope that we can use all our experience to pursue another project,” he says. “Seeing it launch was the end of a pretty long journey for us. But it’s also just the start of an exciting

new one.”

(Credit: Lucia Rodriguez de Torres ’26)